SECURING ELECTRONICS SUPPLY CHAINS: THE CASE OF CRITICAL MINERALS

By Ritika Passi

Critical minerals will power the 21st century industries — and electronics will be at center-stage. Interestingly and equally importantly, the development of the electronics industry will play an increasingly vital role in securing critical mineral supply chains going forward.

The pervasiveness of electronics and a transition towards green economies dependent on clean energy technologies are dictating a shift from a fuel-intensive economy to one dominated by minerals. Countries must move to de-risk and secure their supply chains of these critical minerals that have now become key for economic development and national security. According to India’s Ministry of Mines, “the lack of availability of these minerals or even concentration of existence, extraction or processing of these minerals in few geographical locations may lead to supply chain vulnerability and disruption.”

India is currently pursuing the goal of becoming a global electronics and semiconductor manufacturing hub, with the target of establishing a $300 billion domestic electronics manufacturing ecosystem by 2026.1 It needs to urgently address the role raw materials play in its domestic ambitions and global vision — materials that include critical minerals such as silicon, lithium, iridium, indium, copper, cobalt, gallium, germanium, and rare earth elements. Firstly, tectonic shifts in geopolitics, trade, and investment are not only affecting supply chains of food, fuel, fertilisers, but also critical minerals. Secondly, technology — and the critical minerals embedded within them — have become yet another playground for power rivalry as well as economic nationalism, resurrected in the face of global headwinds, even as the demand for technology is on the rise.

The critical connect

The current urgency for the Indian electronics industry to address upstream considerations arises out of a growing mismatch between demand and supply — but also the sheer content and concentration of minerals going into electronic components and devices.

- Increasing demand

Technology is driving development pathways and the global agenda: from daily devices to systemic-level energy and digital transitions. Just as there is increasing demand for clean, green, digital, and daily technologies, so is the case for the raw materials that power these technologies, everything from chips and batteries to electric vehicles and solar panels.

Electronics system design and manufacturing (ESDM) has emerged as one of the fastest growing industries in the Silicon Age — and an increasingly digitised world, particularly post-Covid, means no likely slowdown. Electronics are among the top globally traded product categories in the world. As per estimates, the global electronics industry is currently valued upward of $3 trillion — around the size of India’s economy. India’s own demand for consumer electronics is expected to increase from less than $10 billion at present to over $120 billion by 2030. Indeed, it is already the second- largest market for smartphones — and as it taps into the significant electronics manufacturing opportunity to generate employment and income, smartphones have become one of India’s top-five export commodities.

Rising demand for the component or equipment means rising demand for inputs. According to the World Bank, global demand for lithium could rise anywhere between 13 to 51 times from current levels. The IEA predicts demand for rare earth elements could increase between three to seven times by 2040. The market for indium, a rare and expensive corrosion-resistant metal used to generate light and colour on our screens and displays, is expected to double this decade.

Moreover, electronic devices, components, and equipment permeate all sectors of the economy. The government has rightly recognised that they are important for the development of other economic or strategic sectors, such as telecommunications, energy, mobility, and defence. Electronics are implicated in existing (such as electric vehicles) and emerging technologies (think sensor-based Internet of Things, for instance).

And these sectors, too, are growing. For example, a 2016 report co- authored by NASSCOM estimated that the aerospace and defence industry will consume electronics worth upward of $70 billion by 2030.

- Growing supply risks

Firstly, it bears asking whether there is enough anticipated supply of critical minerals to meet the world’s appetite for technology. Global demand projections already exceed the rate at which new critical mineral sources are being developed. Copper, the lifeline of electronic circuitry, and even aluminium, a prominent material used across electronic devices, may run out — even with 100% recycling and reuse — unless new sources and mines come online.

Secondly, the COVID-19 pandemic, the Russia-Ukraine conflict, and a worsening US-China systemic rivalry have exposed supply chain vulnerabilities arising from over- dependence.

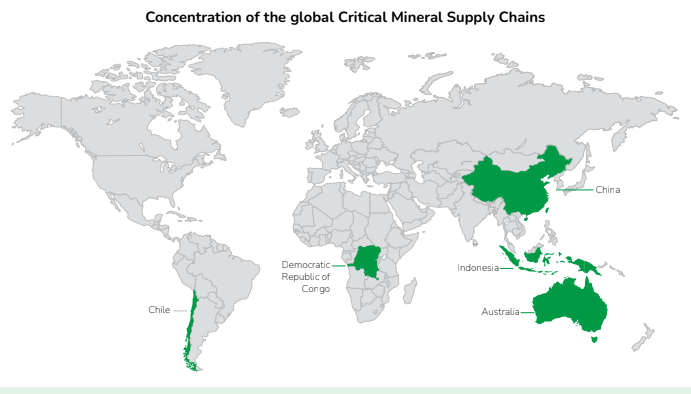

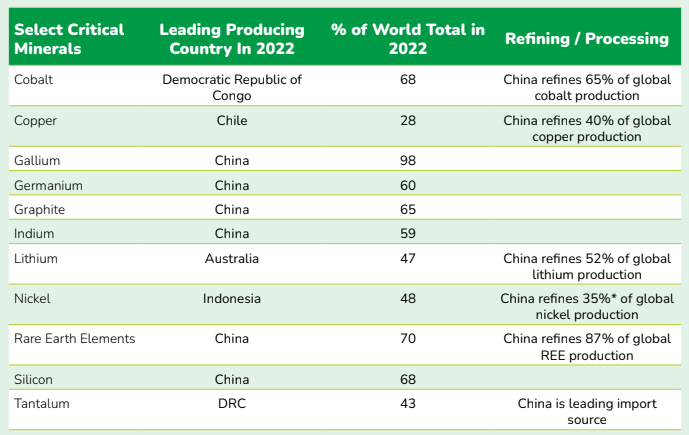

The production and processing of critical minerals are more globally concentrated than oil and natural gas. China currently dominates several critical mineral markets of importance to the electronics industry. For example, it accounts for at least 60% of global rare earth’s production and refines 40% of the world’s copper, 59% of the world’s lithium, and 73% of the world’s cobalt.

Further complicating availability are technical and environmental barriers to entry by other sources. Lithium, for instance, is expensive to extract. Gallium and indium cannot be recycled at present.

Bottlenecks arising out of this concentration and over-dependence are already in plentiful evidence. Take Peru, for example, which accounts for 10% of global copper supply. Recent political unrest has led to the suspension of operations in one of the mines earlier this year.

More worryingly, as countries seek to secure critical mineral supply chains, they are adopting a range of economic security measures and policies — from trade weaponisation to economic nationalism — that threaten stable and secure supply (not to mention the impact on prices).

China’s recent salvo in the ongoing US-China tech and trade war is a case in point. It produces 60% of the world’s germanium and 80% of the world’s gallium and has now put in place restrictions on its exports. These materials are used predominantly in electronics, such as semiconductors and LEDs. Another example is the US’s Inflation Reduction Act, which has introduced specific critical mineral requirements. Such measures could escalate in the time to come and further disrupt existing supply chains and affect market prices.

National security concerns are leading major critical mineral-producing and consuming countries to begin realigning supply chains. In short: an uncertain global trade landscape makes urgent the task of ensuring manufacturing and supply chain resilience.

- Content and concentration

Electronics are mineral-rich. The mobile phone — the current poster child of India’s manufacturing drive — is a handy example. As the US Geological Survey notes, more than one-half of all components in our smartphones are made from mined und semi-processed minerals. The display contains silicon, indium, tin, gallium, and germanium. The electronics and circuitry are copper, silicon, tantalum, und tungsten. The battery: lithium und graphite. Speakers: rare-earths. Semiconductors, a core component of electronics und a new priority focus for India, also require a range of minerals: silicon, gallium, arsenic, and cobalt.

The potential for urban mining — as a means to secure a circular source of critical mineral supply — is enormous. By one measure, electronic waste the weight of 19 Eiffel Towers is discarded every day — but the contents of electronic waste are “as varied as they are valuable, containing up to 60 unique elements.” Effectively, e-waste is a far richer source of critical minerals than natural deposits.

The industry imperative

The electronics industry stands at the forefront of India’s current mission to mobilise domestic manufacturing. As a successful first mover to capitalise on the opportunity for India, it is now well placed to lead and become an instructive example for India Inc. on how to navigate critical minerals and ensure end-to-end supply chain security.

The Ministry of Mines recently released a list of 30 critical minerals for India based on measures of economic importance and supply risk. Encouragingly, the process entailed an inter-ministerial consultation to identify sector-specific minerals: the Ministry of Electronics & Information Technology (MeitY) was also consulted. The list includes several minerals of specific importance to the electronics industry.

Much like other countries around the world, the Indian government, too, is currently working towards creating an institutional architecture and strategic vision around critical minerals to translate into facilitating policies — to de-risk and secure their supply chains for industries, strengthen national security, and contribute towards Atmanirbhar Bharat.

Now, industry must also come to the fore to help define and shape policy pathways towards these ends.

The electronics industry, must, for example:

- Identify an exhaustive list of sector-specific critical minerals to confirm criticality. It will need to map usage and concentrations, any existing and potential domestic reserves as well as mined and refined quantities, potential for recycling and substitutability, and align these with current and anticipated market demand and import/export volumes. This will allow the industry to track developments and trends, assess opportunities and challenges, and identify actionable insights with respect to critical minerals.

- Ensure alignment between industry strategy and targets and mineral-specific plans of action. At present, India’s ambitious $300 billion electronics strategy is being defined as “broadening and deepening” electronics manufacturing in the country. To this end, a 2022 ICRIER- ICEA study recommends the electronics sector first globalise before localising. For example, India is “well on its way to become a leader in the mobile device market of the world and play a major role in India’s electronic exports,” as has identified India’s communication minister Ashwini Vaishnaw. But as India moves from assembly to increased value addition and even indigenisation — such as in the case of semiconductors — which critical mineral will play what role in the domestic ecosystem? Which critical minerals will be mined or refined, stockpiled or recycled, or sources diversified — and how will timelines align with the electronic sector’s strategy and approach? For instance, India is looking to increase domestic production of rare earth elements (REE), but, as per the International Energy Agency, an REE project takes an average of 16 years to come online from scratch. Another pertinent illustration: India at one point used to produce gallium as a by-product of aluminium. Is there a potential to restart domestic production?

- Prioritise recycling electronic waste to build supply chain resilience and enhance security, as identified above. Every year, over 17 million TV sets, 148 million smartphones, and 19 million audio devices are sold in India, and it currently ranks as the third-largest e-waste producer after China and the US. It is time for India to enhance efforts to make urban mining more cost- effective than virgin mining. More broadly, the electronics industry should invest towards creating step-change technological opportunities in the critical minerals space — those that will both lower risk for India in case of supply disruptions, but also enhance Indian competitiveness in the electronics sector globally. For instance, iridium (member of the platinum group of elements, also classified as critical on India’s list) is currently used to light up smartphones and TV screens — but it is the rarest naturally occurring element on Earth. The much more abundantly-found copper has been identified as a possible alternative.

- Explore and outline how India’s emerging bilateral and plurilateral critical mineral partnerships can tangibly benefit and promote India’s electronic supply chains and champions.

Author:

Ritika Passi is a geo-economics analyst and currently a Network for Advanced Study of China (NASC) Fellow at The Takshashila Institution.