FROM BUDDING TO THRIVING: RATIONALISING FACTOR REGULATIONS FOR ELECTRONICS MANUFACTURING

By Bhuvana Anand, Sargun Kaur, Shubho Roy, & Abhishek Singh

The Government of India has set a target of tripling electronics production from $101 billion to $300 billion by 2026. To this end, the government is currently focusing on two approaches. The first approach involves offering fiscal benefits like capital subsidies and production-linked incentives, and the second approach involves process simplification by promoting ease of doing business (EoDB) in the country.

Both these approaches help attract investment to the country but these investments can be substantially better utilised and given a boost. This requires a review of existing regulations and standards, particularly for buildings and employment. Rationalising standards makes no demand on government coffers and can have an outsized impact.

For example, an Indian factory could increase its floor space by 100% by liberalising building standards. Similarly, Indian workers could increase their yearly earnings by 60% by liberalising regulations on working hours.

This article shows how regulatory standards restrict industrial efficiency and job creation in the electronics manufacturing sector.

Building standards hurt industrial productivity

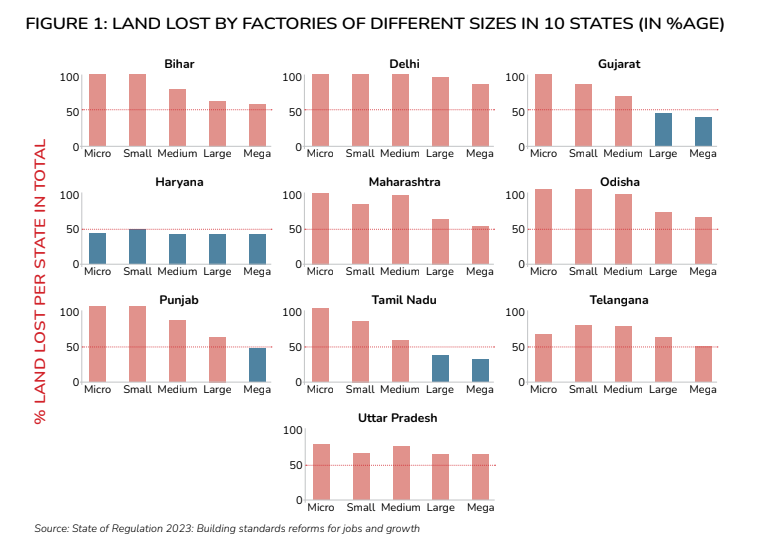

Indian building regulations limit an electronics manufacturing firm’s ability to use land productively and generate employment. A factory in India is likely to lose 50% of land, or more, to building standards.3 Figure 1 shows the percentage of land lost by factories of different sizes in 10 Indian states. These building standards make us uncompetitive compared to electronics manufacturing successes like Singapore, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Seoul which have long relied on high-density industrial buildings enabled by regulatory standards cognizant of the economic needs of the country.

Flatted factories: an example

To set up high-density industrial buildings, one innovative setup used by the East Asian tigers is a flatted factory. These factories are multi-storeyed manufacturing facilities with high worker density located closer to urban areas allowing easy access to city amenities. These factories constitute approximately 70% of industrial floor space in Hong Kong.

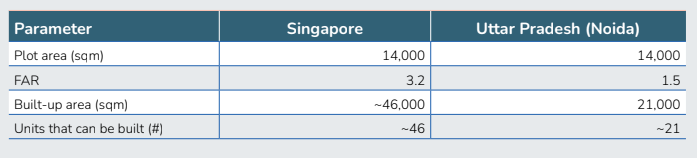

However, India may not be able to replicate this success because of our regulatory environment. A critical constraint that harms flatted factories in India is the floor area ratio (FAR) which determines the factory floor area that can be constructed on a piece of land. The following illustration shows how a flatted factory currently based in Singapore will lose out on critical floor space were it to set up the unit in Uttar Pradesh. Consider the flatted factory set up by Mapletree at 16 Kallang Place, Singapore. This factory is on a 14,000 sqm plot with 46,000 sqm of floor space. If Mapletree built the same factory in Uttar Pradesh, it would have 21,000 sqm of productive floor space (Table 1).

TABLE 1: COMPARING PERMITTED BUILT-UP AREA FOR A FLATTED FACTORY IN SINGAPORE AND UTTAR PRADESH

To encourage factories, Uttar Pradesh has provided fiscal incentives. However, these incentives do not offset the loss due to restrictive building standards. For example, Uttar Pradesh offers a 50% exemption from stamp duty to industries being set up in Noida.6 Let us assume that the same Mapletree factory is set up in Sector 63, Noida. Per circle rates, the factory will get a stamp duty exemption of Rs 2.15 crores. However, the same flatted factory will incur a loss worth Rs 110 crores due to restrictive FAR regulations based on circle rates.

This problem is not peculiar to Uttar Pradesh. Even as other states like Rajasthan, Andhra Pradesh, and Karnataka want to encourage flatted factories, their impractical building standards do not allow such facilities to proliferate.

Labour regulations limit production efficiency

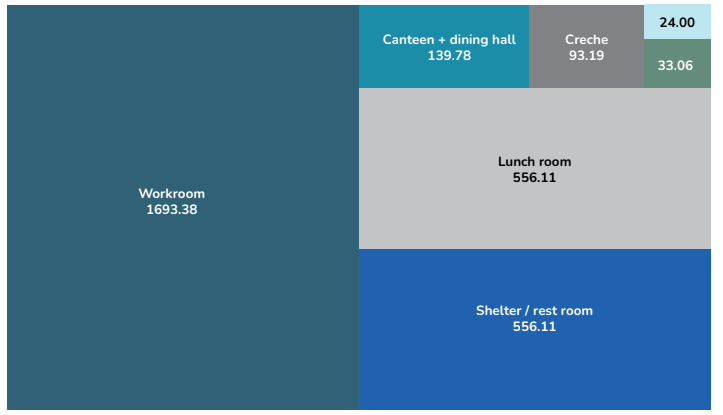

Similarly, electronics manufacturing in India is stymied by labour regulations which make production operationally difficult. Working hour restrictions in India hurt operational efficiency and workers’ ability to earn more. Regulations on working hours force factories to carry out production in 8-hour shifts. Factories can run longer shifts by offering overtime or increasing the work shifts to 12 hours, as in the case of China and Vietnam. In India, overtime work is restricted by hours, and the premium is prohibitively high making overtime work practically infeasible. To make matters worse, firms are forced to set aside 30–45% of the factory building for various welfare facilities (Figure 2). Last but not least, electronics manufacturing firms are also impeded by regulations that make it difficult to employ women and set up temporary employment arrangements.

FIGURE 2: SPACE NEEDED FOR WELFARE FACILITIES IN A 501-WORKER FACTORY IN TELANGANA (IN SQM)

Effects of restrictions on hiring women

Electronics exporting powerhouses such as Taiwan, South Korea, and Vietnam, have historically relied on female workers to succeed in electronics manufacturing, but India has not been able to fully realise this opportunity. Like the case of flatted factories, Indian regulations restrict the employment of women, harming both women and the sector. The law hurts the interest of the industry and female job-seekers in two ways—by hindering the employment of women in night shifts and in several factory processes.

Electronics manufacturers prefer to employ women workers given their greater precision abilities. However, only 12 Indian states allow factories to employ women at night. Even in these 12 states, factories are required to comply with unrealistic requirements. For example, factories in Tamil Nadu must staff 2/3rd of the workforce and 1/3rd of the supervisory staff with women each night. It is unlikely that factories in India will be able to meet this minimum requirement, particularly the minimum requirement for supervisory staff. In contrast, South Korea only requires women’s consent for women to be employed in the night shift.

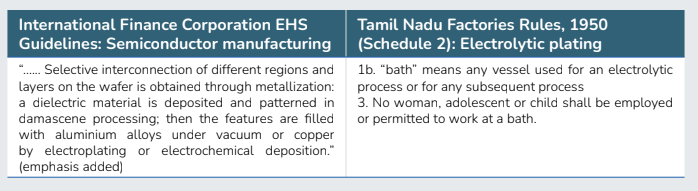

In addition to working night shifts, women are also prohibited from working in certain processes of the electronics manufacturing industry. Consider electroplating, a common and essential step in electronics manufacturing. Women in Gujarat, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu are prohibited from working in any process that involves electroplating (see Table 1).

TABLE 2: REGULATIONS ON HIRING WOMEN

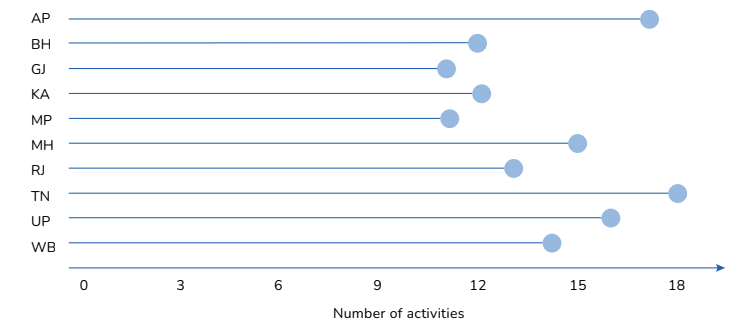

Women are not just prohibited from participating fully in the manufacture of semiconductors, India’s 10 most populous states prohibit women from an average of 15 industrial activities (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3: NUMBER OF PROHIBITED INDUSTRIAL ACTIVITIES FOR WOMEN IN INDIA’S 10 MOST POPULOUS STATES

Effects of laws regulating flexible employment arrangements

Temporary employment arrangements have been a common feature of electronics manufacturing across countries leading in the sector. To compete globally, electronics manufacturing firms have had to build the capacity to produce a high volume of goods in progressively shorter periods. For instance, demand for the latest iPhone is the highest in the first few months after launch, and rises during holidays like Christmas and Thanksgiving.

To meet such demand shocks, firms must have flexible hiring policies. Consequently, temporary workers make up at least 60% of all workers in electronics manufacturing across countries. Indian factories also prefer to employ temporary workers to mitigate the cost of size-dependent labour regulations and to ensure operational efficiency.

Indian regulations restrict the supply of temporary workers by requiring suppliers to repeatedly seek authorisation and maintain extensive records. Under India’s contract labour law, a labour contractor/staffing firm must procure a new licence for each client each year. In contrast, a labour contractor/staffing firm in Vietnam has to get a single licence for all its clients which is valid for five years. Labour contractors/staffing firms in India must also maintain 7 registers and submit half-yearly returns for each client. In contrast, a labour contractor/staffing firm in Vietnam needs to submit only two half-yearly returns and one yearly return, regardless of the number of clients.

Indian lawmakers have acknowledged that compliance requirements for labour contractors in India are overly cumbersome:

“The concept of a single all India licence with 5 years validity de-linked with work order has been proposed as an option available for contractors who undertake a project or are supplying human resources. At present a number of licences are being obtained by a contractor for each work order. (The reform) Promotes ease of doing business. Reduces corruption and reduces paperwork as well.” (Introductory remarks, Report of the Standing Committee on Labour on the Occupational Safety, Health and Working Conditions Code 2019).

Indian regulations also increase the operational cost of supplying temporary workers. In India, labour contractors/ staffing firms must provide temporary workers with rest rooms and canteens. In addition to increasing costs, these requirements create legal confusion since factory owners are already required to construct resting rooms and canteens for all workers. For instance, factory owners are required to provide canteen facilities in factories with at least 250 workers. If a labour contractor/staffing firm supplied 100 or more workers to this factory, then the labour contractor/staffing firm is also legally obligated to provide canteen facilities. It is not clear if the labour contractor/staffing firm is permitted to offset their duties against facilities already provided by the factory.

Conclusion

India has experienced remarkable growth in electronics production, experiencing a 17% Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) over the past nine years. To hit the $300 billion target by 2026, India needs to improve the efficiency of business operations in the electronics industry and become a favourable destination for investment.

This endeavour necessitates the use of high-impact reform approaches. The current initiatives focused on fiscal incentives and process simplification have improved the business environment, but the fundamental regulations/ codes need to be looked afresh to catapult electronics manufacturing capability. The Union and state governments must consider the impact of rationalising standards and controls that can help India to become as competitive as East Asian successes like Singapore and Vietnam.

Our standards often surpass standards set by countries which are 10x India’s per capita GDP. This regulatory baggage may be hampering our efforts to boost electronics manufacturing. Labour and land use regulations prevent manufacturers from expanding production scale in the first place. Rationalising standards that deter growth can help our factories unlock productive land, increase employment opportunities, and grow from dwarves to giants.

About the Author:

Bhuvana Anand, Sargun Kaur, Shubho Roy, and Abhishek Singh are researchers at Prosperiti. Prosperiti builds state capacity to increase economic freedom in India.

Email: info@prosperiti.org.in

I wanted to compose you a bit of remark so as to give many thanks again considering the pleasing suggestions you have provided on this website. This has been certainly open-handed of people like you to deliver unreservedly just what many of us might have advertised for an e-book to help make some dough on their own, and in particular now that you might have tried it in the event you decided. The things also acted as the good way to be sure that many people have similar zeal just like my personal own to find out somewhat more with regard to this matter. I’m sure there are millions of more pleasurable periods up front for individuals who scan through your blog post.