Electronics Mantra: First Globalise, Then Sequentially Localise

By Dr. Neha Gupta

With the domestic market of mobile phones now being catered to by local production, the Government of India’s outlook changed from import substitution to export orientation to capture the global markets with the introduction of the PLI.

Production Linked Incentive(PLI) scheme is now professed as the new industrial policy of India. The electronics sector became the first recipient of PLI, which started in April 2020 with a focus on mobile phones and specified electronic components. Fortunately, India has emerged as the second largest manufacturer of mobile phones, whose production increased from USD 3.1 billion in 2014-15 to USD 38 billion in 2021-22. During the same period, smartphones’ exports have risen sharply from just USD 0.23 billion to USD 5.8billion

There vival of the electronics sector in 2017-18 was initiated by the Phased Manufacturing Programme (PMP) which was introduced as an import substitution strategy and became one of the biggest contributors to the growth of the sector.

With the domestic market of mobile phones now being catered to by local production, the Government of India’s outlook changed from import substitution to export orientation to capture the global markets with the introduction of the PLI.

The government in fact has been adopting a number of trade and industrial policy initiatives starting from the National Policy on Electronics (NPE) of 2012 (revised in 2019) and the Vision Document prepared by the Ministry of Electronics and IT (MeitY) and India Cellular& Electronics Association (ICEA) released in 2022. Their core motivation has been to enhance India’s economic development, create more output and jobs, and increase competitiveness. Accordingly, the focus has been on achieving maximum success in the case of the ultimate indicator, i.e., the domestic value addition(DVA).This indicator is estimated as the sum total of the value of all domestic inputs (labour, capital, management, etc.) used in the production process.

Although, increasing DVA is a common practice, Indian policymakers have gone further to simultaneously influence the two components that make up the DVA, namely the quantum or scale of exports (SCALE) and the domestic contents per unit of production (DVA ratio: equivalent to value addition in aggregate). That is, the government has been encouraging policies like PMP to substitute the use of imported inputs with domestic production. While not a requirement, the PLI scheme for the sector is expected to increase DVA ratio, say for mobile phones from 15-20% to 35-40%. Concurrently, along with the target of having more local content and domestic electronics production of USD 300 billion by 2025-26, the Indian government also aims to achieve exports of USD 120 billion to transform India into an electronics hub.

In a nut shell, the government hopes that both objectives can be simultaneously pursued, such that the rise in DVA ratio should not adverse affect the goal of achieving exports SCALE and vice- versa. Does this assumption hold true for successful exporting nations and for India? As policy measures swing heavily between raising DVA content and exports, policy makers in India face a situation similar to which came first, or rather should, the hen or the egg. Our recent report ‘ Globalise to Localise’ , prepared by Indian Council for Research on International Economic Relations (ICRIER) in collaboration with ICEA, provides a more plausible explanation for the same using the case of the Indian electronics sector.

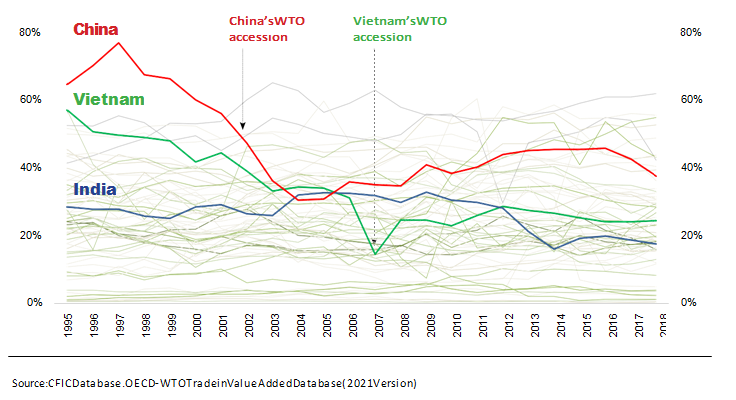

Although India’s DVA ratio economy- wise, for all the sectors, is 80% , which is near to 87% of China, its local content ratio is lower for its electronics sector at just 18%, i.e., only 18% of the value added in the electronics sector was generated within India as compared to 38% in the case of China and 24% in the case of Vietnam (Figure 1). This, however, also supports the nature of the electronics trade, which is more global value chains (GVCs)- dominated. Greater participation in GVCs means smaller DVA ratio and higher scale and vice-versa. Experiences of Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, etc. have clearly shown that trade policies should not focus on exporting products with more value addition.

The impressive results of policy measures are more visible in the case of India’s electronics exports, which have almost tripled between 2015 and 2022 from USD 5.8 billion to USD 16 billion. But, as India plans to achieve the size and pace of exports attained by successful exporting nations such as Chinaand Vietnam, who respectively exported USD 902 billion and USD 131 billion worth of electronic products in 2021, there is an ongoing urge among Indian policy makers to substantially increase exports and capture global markets.

Policy makers are not only concerned about India’s lower exports languishing in the range of USD 10 16 billion annually but also about its continuously lower DVA ratio, i.e., 18%. This placates India’s back-to-back policy initiatives to simultaneously boost both to manifest desired realities on both fronts.

Figure 1: India’s DVA ratio for the electronics sector has been relatively low and stagnant as compared to China and Vietnam

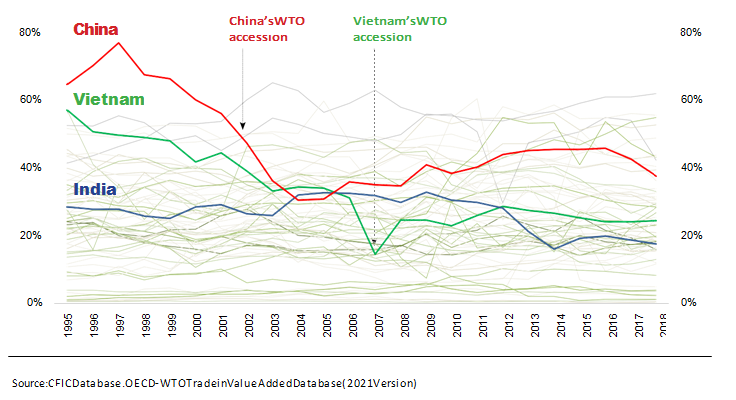

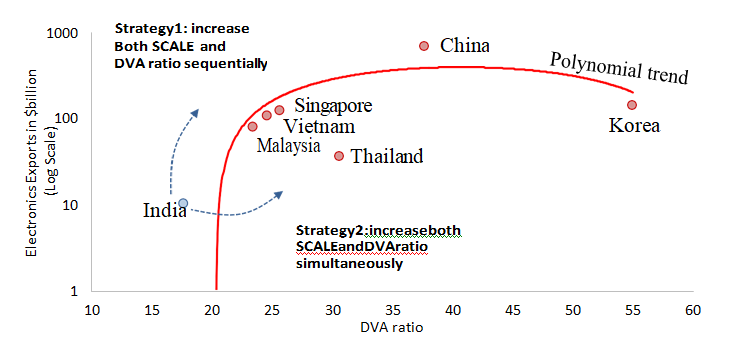

That said, the ICRIER- ICEA report particularly conducted a cross- country regression analysis to examine the empirical relationship between exports and the share of domestic value addition in successful exporting nations. The results show a strong perverse correlation between SCALE (exporting to the global market at scale) and DVA ratio, even after accounting for open trade policies and domestic reforms. The two variables are found to be negatively correlated in the short term (Appendix 1), while they reveal a positive correlation in the medium term(Figure2).The reason being, it is not a laid-back task to increase DVA.

Not ably, India and China are operating at a contrary spectrum when it comes to electronics trade and GVCs, as the latter corresponds to high SCALE and high DVA ratio, while India still exhibits a less dynamic relationship between these two variables.

Figure 2: China, India and Vietnam have pursued different approaches for local content and exports of electronic products, 2000-20

Source: CEIC Database, OECD-WTO Trade in Value Added (TiVA) Database Note: DVA shares for 2019 & 2020 are assumed to be same as that of 2018

The knowledge that we pushed forward is that the current path involving a simultaneous increase in exports and greater use of domestic content is unlikely to put India on the same trajectory as China and Vietnam, especially in the absence of a competitive domestic eco system of ancillary suppliers. This is because the trajectory followed by East Asian nations has been totally opposite. To explain, there have been efforts to lower local content requirements (LCRs) or DVA ratio by China and Vietnam to attract investments, gain entry into WTO and be better linked into the global supply chains(see Figures 1 and 2).

Successful electronic exporters in East Asia, including these two, have followed a different rule than India (as indicated clearly in Figure3) of first trying to achieve global scale in exportin the initial years of development (short-run), even ifit means having lower local content. And, gradually once SCALE is achieved, then their emphasis shifted to increasing DVA to the higher levels (medium- to long-run).

Parallel consistent efforts have also been intensely incorporated by them to do root-level healing for robust domestic competitiveness while remaining focused on SCALE. This is because they realised the fact that DVA rise takes time, for which the country gradually needs to build a competitive ecosystem of suppliers and investors. The regression analysis also shows that it is not easy to change DVA just by policies. This realization is inevitable for the Indian government, policy makers and industry bodies engaged in the electronics sector.

Figure 3: Successful countries have first achieved SCALE before increasing DVA ratio

Source: World Bank, OECD- WTO Trade in Value Added Database

Note: DVA for 2019 & 2020 same as 2018; Trend line is from 2010 to 2020

An alternative approach of “first globalise, then localise” in the case of the Indian electronics sector is thus suggested in the Report. This approach has strong empirical validity and will involve following the two sequential phases, i.e., the immediate goal should be to export at scale to the global market (globalise) and the subsequent objective could be to increase the share of local content (localise).

To explain, in the short-term, in phase one, India must focus to achieve SCALE with the export target of at least USD 30 billion (found on the basis of lessons from successful East Asian countries, see Figure 3). This would mean temporarily suspending localisation requirements, removing duties on intermediate items, and accelerating integration through bilateral and regional FTAs. The idea is that the sector should be able to source inputs from the lowest-cost suppliers anywhere in the world until it achieves a global scale.

Once global SCALE has been achieved, the policy emphasis in the second phase could be to encourage greater use of local content or increase Domestic Value Addition (DVA ratio).But this will have a longer gestation period. So, along with the priority of exports expansion, the government should create a competitive domestic ecosystem of ancillary suppliers by using clear-cut strategies(Box1).This must involve a technology upgradation programme, sourcing fairs, supporting industry development programmes, and workers training at scale. Just hiking customs duties will only feed protectionism and not sustained growth.

Conspicuously, the Indian electronics sector is now also exhibiting the deep urge in India to gain maximum benefits from globalising trends and ride the manufacturing bus that it had failed to catch in the past 30 years. ‘Strategize each Policy foot step’ should be the mantra of the Government of India. Cooperative collaboration by the state governments and the private sector is the right intention seed to grow the domestic ecosystem and push exports aggressively and then gradually march towards the ultimate need of increasing local content. The success of Indian electronics could then work as a rule book for many other developing countries that struggle to have competitiveness at home and at abroad.

1- Policies to achieve global scale

- Promote bilateral and regional FTAs

- Reduce or rollback custom duties on intermediate inputs

- Temporarily suspend policies that insist on local content

- Temporarily remove place- based restrictions on intermediate inputs

- Targeted and temporary fiscal incentives like the PLI programme

2-Policies to increase local content

- Announce a strategy to develop the domestic ecosystem that involves a technology upgradation assistance programme, sourcing fairs, supporting industry development programme and workers training at scale

- Set clear targets and timeline for upgrading domestic suppliers tonier I and II suppliers

3- Policies that are important for both scale and local contents

- Macro- fiscal stability

- Competitive exchange rate

- Ease of doing business

- Lowering/reducing regulatory burden and reducing cost of transport and logistics

Author

Dr. Neha Gupta is a Fellow at ICRIER with a specialization in international economics, focusing on the dynamics of global value chains (GVCs), India’s export competitiveness in the manufacturing sector, FDI, and trade in yoga services. She has a Ph.D. degree in Economics (on GVCs) from the Indian Institute of Technology Delhi (IIT Delhi).

I have been reading out a few of your stories and i can state pretty clever stuff. I will surely bookmark your site.